If you hang out in an art school, you hear lots of talk about “art as discourse.” It’s a thought that is almost worn out, yet ideas become commonplace because they are apt. And sometimes an artist can extract a combustible bit of material from the ashes of cliché. In their playful, collaborative work Object Lessons (2012) Robin Hill and Ulla Warchol (working together as Biolunar L) tease the notion of “art as discourse” to life.

Biolunar L, Object Lessons, 2012 (overview)

Detail from Object Lessons

Object Lessons is a collection of 24 things, arranged together in a vitrine. It’s hard to tell what they are. Each thing is composed of other, recognizable things—a dried lemon, a memo skewer, thread. Individually the parts make sense. But their syntax, their order in relationship to each other, skews what they have to say.

Detail from Object Lessons

That lemon, which on my counter would say “compost,” says something else when it is perched on a spike, wearing a midriff halo of balls dangling threads. It says a lot of things simultaneously: orbital model, carnival, scraper wheels. It says “whirl” and “balance;” “swing” and “lift,” grabbing associations from different corners of experience and and flickering between scales from macro to micro.

But it’s not only in “reading” the parts together that this collection constitutes a “discourse.” Hill and Warchol, long-time friends who are now separated from each other by the breadth of eight states, literally used the objects to “talk” with each other. They both had, as artists will, collections of “interesting stuff” in their studios, objects that were stuck in limbo—too inspirational to toss, but not inspirational enough to have become actual work. Anyone who has made art themselves would recognize the genre. It includes remainders, like a white plaster disk from the bottom of a bucket used to cast something else; souvenirs, like an English needlebook; and worthless treasures, like a junk-drawer box with buttons, feathers, and dried-out rubber bands that Warchol’s children scoured from under a table at the Lambertville, New Jersey flea market.

Screenshot from Object Lessons Skype conversation

To get Object Lessons going, Hill and Warchol defined a system. First, they each gathered twelve cool but orphaned objects from their studios. Then they made a cross-country Skype exchange, in which they simultaneously held up an objects for each other to view. The ground rules for this conversation-through-things were 1) No discussion beyond description of physical properties (weight, size, texture, smell, taste, color….) 2) Try to really SEE the object being shown 3) Make a work from the object shown incorporating something noticed about the object seen. Eventually, the artists joined up in Hill’s studio and unveiled the object-responses to each other.

The viewing ritual was documented in a small book with screen grabs from the Skype exchange, but you don’t need the book to perceive the relationships. If one sliced open the mummified lemon, for example, you would have the structural model for the tube created from the Karamelle advertisement, which has a balsawood armature based on the inner membranes of the fruit. It’s a sort of stretch-limo of a lemon shape, and it’s funny.

Cover of Joint Attention, edited by Axel Seemann

I loved the sly humor and friendly feeling that floats through the piece, but Object Lessons really caught my attention because I’ve been mulling over a concept from psychology called “joint attention.” As defined in Joint Attention: New Developments in Psychology, Philosophy of Mind, and Social Neuroscience, edited by Axel Seemann and hot off the MIT Press, joint attention is “the capacity to attend to an object together with another creature.”

A lot of subtle thinking is folded into this short definition. For example, simply looking at something at the same time is not joint attention. As psychologist Michael Tomasello writes, “A sightseer and a mountain climber attend to very different parts of a mountain (e.g. to its coloration or its slopes) in light of their very different goals.”

Psychologist Inge-Marie Eigsti, who studies the interaction of language and brain development, tells her students that joint attention “is critical for social development, language acquisition, and cognitive development…“, and it has become an important topic for research in part because difficulties with joint attention may be connected with autism. Eigsti, like most psychologists working in this area, studies children. But as an artist/writer who spends a fair amount of time looking at people looking at art, I’ve been wondering if there is something about art that stimulates, exercises, or develops joint attention in a particularly adult way.

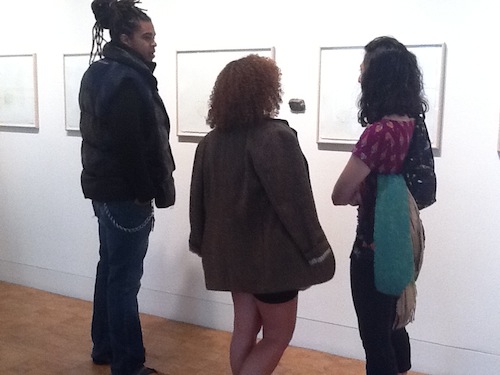

Viewers at the John Cage exhibition, Crown Point Press, San Francisco

Many of our uses for art are not social, of course. Watch exhibition-goers and you will notice different kinds of attention. Some people are speeders, glancing at each object for a second. Some people are skippers, looking at just a few works, guided by taste or an audio tour. And some people are soakers, contemplating everything. Then there are the socializers, who come in two types: those who are chatting about something else as they stroll through the show, and those who are interacting simultaneously with the works and with each other. It’s this latter group I’m curious about; perhaps they are having an echo of the experience that was purified, intensified, and turned into art by Object Lessons.

Does an exchange mediated through objects help people think together? Do the challenging complexities of art OBJECTS, in particular, increase the odds of joint viewers skidding together into insights they would never, otherwise, have experienced? It’s my bias to think so, which doesn’t mean that I’m not equally interested in art ACTIONS, just that I think that objects offer distinct opportunities that may be related to subjects like joint attention and social cognition. In an upcoming post I will tackle a possible problem with this idea, raised by Dr. Anjan Chatterjee, but in the meantime let’s hear what Hill and Warchol have to say about the outcome of Object Lessons.

Detail from Object Lessons

In the introductory essay to the book, they write, “Upon Warchol’s arrival in California the artists structured an unpacking session in Hill’s Woodland studio, in which the transformed objects faced each other for the first time. What emerged was a tender and surprising experience of reciprocity.”

“We felt seen,” they told me. This is a rare and precious feeling. As neuroscientist Antonio Damasio writes, “The fact that no one sees the minds of others, conscious or not, is especially mysterious.” Object Lessons walks us right up to this mystery of what we cannot know about each others’ thoughts, and the pleasures of signaling to each other, anyway.

Object Lessons by BiolunarL is on view in the exhibition “Left to Chance: In Search of the Accidental Book Art,” curated by Hanna Regev, at the Austin Burch Gallery of the San Francisco Center for the Book, 300 DeHaro Street, San Francisco, CA, USA, through May 12, 2012.

All images not otherwise identified are of the work Object Lessons, 2012, by BiolunarL. Courtesy of the artists.

Links:

Robin Hill’s website http://robinhill.ucdavis.edu/

San Francisco Center for the Book http://sfcb.org/