A couple of posts ago I wrote something snarky about Freud, which he himself did not deserve. A great thinker, he’s entitled to his museums. But while clambering over the heaps of theory built on his work one might be forgiven a bit of fatigue. Scholars strain to patch up his ideas: the Oedipus Complex is presented; the Oedipus Complex is hastily critiqued for its weird ideas about women. But really, what’s the point?

Franz West, Liège, 1989

Liège, an iron couch, is part of the permanent collection of the Sigmund Freud Museum.

Photo copyright: Gerald Zugmann

Remember that Biblical parable about building one’s house on the sand? There is no shiftier sand than the patriarchal, colonial culture of Freud’s milieu. Might it be possible to stand back from the great edifice of theory tweaking Freud’s thought into something we can use today and say, hey—let’s move into another neighborhood, instead of hammering braces onto this rickety structure.

Why, you may ask yourself, is this an issue for an essay on contemporary art? Yes, whatever we mean by “self-expression” must be bound up with what we mean by “self”; but we no longer think of art as “self expression” just as we no longer take the Oedipus Complex as gospel truth. Perhaps you regard Freud’s insights as old news, his missteps likewise. But have you recently commented on someone’s big “ego”? Or observed that so-and-so had a “death wish”? You can thank Sigmund for that. Or not.

My “John the Baptist” moment

Freud’s ideas were so generative in their time that they are pervasive in our time. We use them without thinking, entangling our consciousness with the consciousness of 19th century Vienna. That is why, despite its sometimes annoying convolutions, theory has been useful for artists and other people who want to get under the hood of our culture and make a few repairs. The writings of thinkers like Jacques Lacan and Edward Said became material for artists like Mary Kelly and Yinka Shonibare MBE, who wanted to get at cultural blindspots, the cultural “unconscious” if you will. Except maybe you shouldn’t…since the “unconscious” is, also, a Freudian concept.

Yinka Shonibare, MBE, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews Without Their Heads, 1998

©1998, Yinka Shonibare, MBE

It seems like an impossible project, filtering out ideas that have soaked so deeply into our culture. But it’s a project that will, I think, take care of itself by becoming irrelevant. Sometime soon someone will do what Freud did, start with contemporary science, test it against the problems we have conducting our lives (including misuse of science), and emerge with a new description of human subjectivity that is true enough, and vivid enough, to push Freudian theory decisively into history. We will use new words to talk about inner life in the 21st century; “id” and “ego” will seem just as period to our descendants as the four “temperaments” seem to us.

What makes me so sure? We can see our body/brain/environment in ways Freud couldn’t imagine and with a level of detail that begins to answer previously unanswerable questions about human subjectivity. We still understand very little of what we see, but compared to Freud, we are rich in data. Yes, imaging techniques such as fMRI have their limits and the claims made for neuroscience sometimes overreach. It doesn’t matter. When you can talk about a visible network of specific interactions, postulating a vague “drive” no longer makes sense. It might not be absolutely incorrect, and it might linger in literature and language. It’s just not the most useful idea available.

New models

But the real reason I predict that a new model for understanding inner life will emerge is that in art, it is already happening, in a diffuse and fragmented way. For the past three or four “postmodern” decades artists have been entranced by the fragmentation, the long moment of transition as old ways break up and new ones gestate. Paradoxically, the artists who seemed most trustworthy, most relevant, were the artists who had no answers. The works that held center stage, such as the films of Eija-Liisa Ahtila and Omer Fast, the paintings of Gerhard Richter or the activities of Rirkrit Tiravanija and the Raqs Media Collective, refused explanation, holding possible meanings swirling in solution.

Yto Barrada, detail The Telephone Books (or the recipe book), 2011.

Photo: Francesco Galli.

Photo courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia

The modernist dream of universal truth was exposed as a nightmare when the “art world” began to include artists and cultures from around the globe. Heavy doses of history and theory came into play; because a common culture could no longer be assumed, references had to be made explicit. When Yto Barrada showed photographs of her grandmother’s notebooks, her explanation of the markings (her grandmother was illiterate, so invented signs to record the phone numbers of her ten children) made them both intensely moving and symptomatic of technologically-mediated communication between people with vast differences in self-concepts and communicative resources.

This contemporary condition, in which people collectively juggle many forms of subjectivity, none of which can be accepted as “truth”—Australian cultural theorist Nick Mansfield calls it “simultaneously believing all we are told and nothing”—has itself been theorized in different ways. If, when exploring an exhibition, you run across words such as “alterity” or “hegemony” you are in this theoretical territory.

New forms of “self,” new forms of “self-expression”?

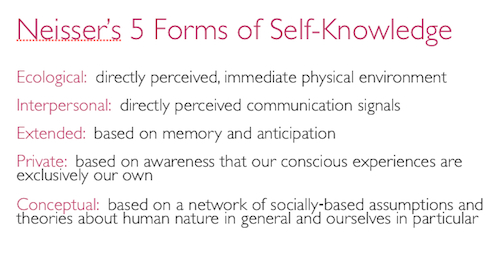

At the same time, “self-expression” dropped into the background as an outdated concern, inextricably linked with modernist notions of “genius” and concomitant, damaging assumptions about race and gender. But what if, just for example, we imported the notion of “five kinds of self” from cognitive psychologist Ulric Neisser?

In 1988, Neisser proposed that, “Self‐knowledge is based on several different forms of information, so distinct that each one essentially establishes a different ‘self’… Although these selves are rarely experienced as distinct…they differ in their developmental histories, in the accuracy with which we can know them, in the pathologies to which they are subject, and generally in what they contribute to human experience.” (1)

One could experiment with a version of “self-expression” based on Neisser’s categories, thinking of Sarah Oppenheimer’s architectural alterations as an expression of the ecological self; Louise Bourgeois’s sculptures as articulating the extended self, Tino Seghal’s conversational performances as framing the interpersonal self, Ryan Trecartin’s psychedelic videos as hinting (perversely) at the private self, and Jompet Kuswidananto’s tableaux of Indonesian trappings as visualizing the conceptual self.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Third Realm, a site specific project by Jompet

Kuswidananto, installed at Gervasuti Foundation, Venice, Italy, 2011

There are problems with this; not least that words such as “ecological” and “conceptual” have accumulated associations that stray from Neisser’s considered definitions. But Neisser’s formulation is only one of the possible approaches to “self” that one could play with, now that the 19th century version has worn sufficiently thin to see through.

Weaving a new “self” with enough stretch to fit a global consciousness is a big job. But I’ll play with tying on the warp in upcoming posts, taking a look at “embodied cognition” and maybe at the utility of “self-expression” in countering “shadow selves” formed in the digital wake of wired societies. First, though I will fulfill a few other promises, topics that were waylaid as I squeezed a century’s worth of philosophy into a thousand words looking to the future.

(1) Neisser, Ulric, “Five kinds of self-knowledge,” Philosophical Psychology I (1): 35-59 (1988)

Home Page Image: Entrance Hall of Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna with view of Liège by Franz West. Photographer: Florian Lierzer. © Sigmund Freud Privatstiftung