It has been shown, by thinkers such as Donna Haraway and Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, that opining about human nature on the basis of primatology research is an excellent way to reveal your deepest, darkest, most unflattering beliefs about human existence.

Closet sexist? Oops—your macho is showing. (See Hrdy’s The Woman Who Never Evolved.) Secretly a bit racist? Not a secret anymore. (Check out Haraway’s Primate Visions). Tantalized by “alternative” sexualities? You might as well march down Main Street in leather gear as theorize about bonobos. (C.f. Ian Parker’s “Swingers“.)

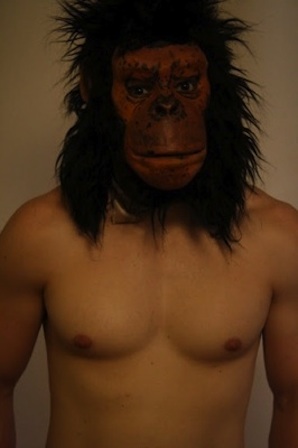

Rachel Mayeri, Still from <em>Baboons as Friends</em>, 2007

So before I promised that today we would take a look at an art opening as a primate gathering, I probably should have gulped and looked for another topic. But ever since I saw the first video in Rachel Mayeri’s Primate Cinema series, Baboons as Friends, I spot nervous students hanging around the fringes of an opening and flash on juvenile apes, figuring out their place in the social structure. If I notice an artist chatting up a prominent curator, I imagine Mayeri’s collaborator, primatologist Deborah Forster, narrating the scene: “The artist and the curator are in consort…the artist at this point already knows that he’s probably going to lose the curator’s attention because it’s near the end of the opening, and as the other power players invited to the dinner hosted by the gallery arrive, the curator will want to talk to them. The curator is very confident, he’s probably getting antsy because the artist’s insecurity is getting in the way of his ability to conduct an entertaining conversation….”

That’s a riff on Forster’s recounting of the primate action in Baboons as Friends, with just a little more than the names changed to make it apply to an opening. There may be truth in this slant on the art world’s favorite social custom, but what good does it do to think of it this way? There are reasonable people out there who get very irritated with suggestions that the study of animals yields useful information about humans. These enforcers patrol the human-animal boundary because blurring it—by classifying some people as “animals”—has often justified human exploitation.

The American edition of Sarah Thornton's best-seller <em>Seven Days in the Art World</em>.

So instead of thinking “animalistically,” we could just go with a primatologist who specializes in humans—i.e. an anthropologist—such as Sarah Thornton, whose 2009 best-seller Seven Days in the Art World (translated into 14 languages) contains many luscious examples of social maneuvering in the art context. For example, on page 222, Thornton records this important art speak at the Venice Biennale, delivered by an unnamed acquaintance: “‘He’s C list. She’s B list,’ he said, as he fingered people out of the crowd. ‘Nick Serota is A list,’ he added for clarification.”

(Sir Nicholas Serota, in case you’re wondering, is the Director of the Tate in Britain.) But crack observer that Thornton is—she took a lot of notes on things her companions probably didn’t think she saw—she doesn’t go deeply into opening culture. Perhaps we could turn to an artist for insight. Peter Davies’s painting The Hip One Hundred (1998) is an oldie-but-goodie satirizing the social sorting that Thornton reports, but Davies doesn’t really address openings, either.

Tom Marioni, <em>Drinking Beer with Friends is the Highest Form of Art</em>, 1970- as shown at the Hammer Museum at UCLA in 2010. Photo courtesy the Hammer Museum at UCLA.

Conceptual artist Tom Marioni’s long-running The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends is the Highest Form of Art (1970- ) (yes, the title is descriptive) could be regarded as a sort of meta-opening, but it is in no sense analytical. Someday Jayson Musson or Alex Bag, both video/performance artists who satirize the art world, may produce the definitive work on openings, but unless I missed something, that hasn’t happened yet. (That I missed something is entirely possible, but I did conduct a great deal of enjoyable research trying to find out…if you’d like to draw your own conclusions, their works are linked below. Let me know if you find a bit I missed.)

Alex Bag, still from <em>Untitled '95</em>, 1995. Photo courtesy Freymond Guth Fine Art.

Are the ins and outs of art openings more comfortably the province of fiction or film? You may recall that Jeff in Venice, a 2009 novel by Geoff Dyer, takes a entertainingly sardonic look at the parties around the Venice Biennale, and(Untitled), a 2009 film by Jonathan Parker, spoofs a very believable gallery opening in New York. But hey, there’s a reason this stuff came out in 2009, in the wake of a big-time boom in the art market and therefore a time when deflating art world pretensions seemed like a particularly worthy project. But the processes I’d like to talk about aren’t predicated on success; I suspect that they operate at openings in student galleries around the world just as vigorously as they do at the Biennales. And a cynical approach, however entertaining, isn’t going to take us anywhere we haven’t already been.

Rachel Mayeri, <em>Primate Cinema: Apes as Family</em> development still, 2011. Photo by Matt Chaney.

So we’re back to primatology. Openings, like other human social forms, have many variations. But they have in common that something novel is on display, and that a group congregates to socialize in connection with the display. Although most openings are public affairs, the attendees tend to have more in common than, for example, a crowd moving through a shopping mall. They are also more different from each other, more varied, than a group of people participating in a private social event—an extended family, or workers at the same company. So the structure of an opening contains an exciting commingling of social possibilities…there are existing relationships to nurture, alliances to strengthen, and also new people to meet, new connections to be forged. There is a common topic of conversation at hand, and of course the wine, to ease social exchange. But no one can pay attention to everyone, so social choices have to be made.

All of of which means that an opening gives our hardwired primate sensitivity to social status a workout. This is not the same as saying that the art doesn’t matter—it does, for all the reasons we might normally think it does and also because it facilitates what psychologists might call “joint attention”—more on that in a future post. But in the context of an opening, it is a rare viewer who isn’t, on some level, aware of the people around her, calculating who to stand next to and who to avoid, and noticing who is and isn’t getting attention from other people. The baboons would understand.

Links:

Alex Bag’s Untitled ’95 (1995), First Semester and Seventh Semester

Jayson Musson (Hennessy Youngman) Artthoughtz Youtube channel

Tom Marioni’s website