In the country, highway sounds can make you feel insignificant. The speed with which vehicles pass you by insists that the life worth paying attention to is somewhere else. It was that distant zoom that I heard on entering Christina Battle’s video installation Dearfield, Colorado (2012), the whoosh of a big truck racing down Highway 34 past a place that used to be a town.

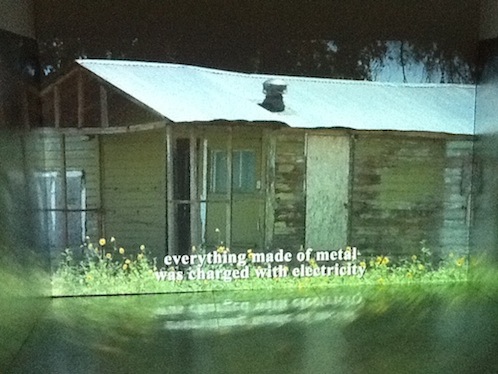

Not just any town, but a town founded in 1910 by Mr. Oliver Toussaint Jackson as an African-American agricultural community. I learned this from Battle’s photograph of a historic marker, hung across from the video projection as if it were a wall label. I turned back from the marker to the video; a black semi zoomed through a crossroads, observed from a standpoint on the dirt street of the abandoned town. When Battle cuts to the near surroundings, it can be seen that the buildings are so dilapidated that some of them are more timber than structure. She takes each shot and holds it, giving the video the look of stills pieced together except for the tremor of her handhold, flying birds, or sunflowers troubled by the breeze. In a slow counter-rhythm to the tour of the ruins, short texts appear over the images:

“The day was warm and dry,

and when a cloud appeared in the evening sky,

many hoped for rain”

“fields sizzled under the metallic sky”

“dust filled the air to a height of 3 miles and filtered into the tightest of buildings”

“everything made of metal was charged with electricity”

These quotes were taken from first-hand accounts of dust storms by people who lived through the “Dirty ’30s” in Colorado and Nebraska. Dearfield, Colorado belongs to Battle’s Mapping the Prairies through Disaster, an ongoing series of installations. The disaster for Dearfield was the drought that hit the Midwest along with the Great Depression. The town, which in the early 1920s had been prosperous and growing, emptied out. When Jackson died in 1948, the town was gone, too.

As Battle was researching the period she noticed an intriguing detail in the stories of extreme drought and massive dust storms: references to the electric quality of the air and the metallic look of the sky. In 2006, researchers at the University of Michigan, Jasper Kok and Nilton Renno, reproduced experimentally the physical processes behind these reports. Dust storms start with wind, but as the grains of sand rub together in an intense storm, they produce electrical fields that lift even more dust into the air. (This may explain the monster dust storms on Mars, too.)

Christina Battle, Dearfield, Colorado (2012)

Video loop, sound, aluminum (still), 9 x 5 ft.

Courtesy the artist

As she developed the installation, Battle looked into building an electrified room that would give static shocks. But, concerned about the risk of hurting people, she settled for hinting at the experience by surrounding the projection with aluminum. The hard, shimmering surface blurs the image, a dry “lake” changing color with the reflections from the video’s skies, the whole ensemble imaging the disintegration of social and structural forms that fascinates Battle. The sound subtly and disturbingly supports this theme. The highway sounds and bird calls have an undertone of static, a signal that whatever peace this place has found is temporary. It’s the sound of “sferics,” radio atmospheric signals produced by lightning strikes.

Battle’s work was one of two video installations in the exhibition Continental Drift at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Denver, Colorado. I was surprised to find that Continental Drift was juried from an open call for work by Colorado artists who were exploring a sense of place. The exhibition’s thematic coherence suggested the guiding hand of a curator. Although the submissions were culled by Nora Burnett Abrams and Jacob Proctor, to craft such a strong show they must have had a great pool of works from which to choose. But if I were a Colorado artist, I would pay close attention to the MCA’s calls, too. “Museum” suggests the past, but this place has the vibe of the future. The airy building, which was built in 2007, is “green” and the presentations inside are both playful and sophisticated, reflecting the philosophy of the MCA’s director, Adam Lerner. (Lerner’s personal mission statement, “Who’s Ridiculous Now?” is my favorite text by a museum director, ever.)

The museum is compact, tall rather than wide, which might explain why the other video installation, Jeanne Liotta’s Observando El Cielo (2007), inhabited a floor of its own away from the other works. But this meant a generous viewing area where the sound could be fully appreciated without headphones, so the trade-off between proximity and prominence worked in the piece’s favor. The soundtrack, by Peggy Ahwesh, is a remarkably powerful match for visuals of the night sky that Liotta spent seven years putting together. Imagine that you are standing outside looking at the sky on a dark, dark night, yet in that sky you are somehow seeing vibrant colors, fuchsias, reds, and super-saturated blues. At times you are standing still but the sky is moving rapidly around you; at times a bright flash washes out your vision; always the night around you is alive with whistles, crackles, snaps, or muffled radio sounds. Liotta’s installation immerses you in a curious relationship with the sky. You are looking at it, you can see and hear that other people are looking at it, but the experience is in no way stable or predictable. As the nineteen minute piece (originally a 16mm film, shown at MCA as HD video) progresses, both sound and image hover right at the edge of “making sense” without ever going over it; each new moment brings surprise.

Jeanne Liotta, still from Observando El Cielo (2007)

16 mm color & b/w film converted to DVD, 19 min.

Soundtrack by Peggy Ahwesh

Courtesy the artist

I am not the first writer to praise Liotta’s film — Chrissie Iles chose it for an Artforum Top Ten in 2007 and Film Forum put it on a “Best of the Decade!” list. But in this show, in conjunction with Battle’s work, a new reading of it emerges. In a way, place IS climate. The associations that give a place personality — sunny Phoenix, rainy Seattle — are so weather-related that one concept can’t really be extracted from the other. Battle gives us a bright Colorado day, with a surfeit of dry sun; the watery mirage created by the aluminum seems like a taunt to a country which has so forgotten its recent history as to waste water and develop wide swathes of country unsustainably. Liotta gives us dark sky as a place characterized by “bolts from the blue” rather than reassuring, dependable cycles. As with most good art, these two works have many levels of interpretation. But in light of “continental drift” (the very name of the show encapsulates the knowledge that “place” is a restless concept) they suggest a double vision of change: attending both to history and to each immediate moment. Most of the discourse about climate change is frightened, speculative, or angry, and with reason. But reason will not help us, at the deepest emotional level, cope with planetary transformation while remaining alive to the possibilities we have left. Works like these just might.

Continental Drift Schedule

Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver Co.

July 13 – September 23, 2012

Aspen Art Museum

October 19 – November 25, 2012

Links

Christina Battle’s website

Jeanne Liotta’s website

An accessible account of Kok and Renno’s research, by Larry O’Hanlon for Discovery Channel