Once upon a time I saw the art critic Dave Hickey defend beauty. At the time, mid-1990s, he was both famous and notorious for The Invisible Dragon, a book of essays in which he attacked the art world for neglecting “beauty” in favor of “meaning.” He found the beast academia, which he described as a “massive civil service of PhDs and MFAs [administering] a monolithic system of interlocking patronage,” guilty on this score.

Hickey’s delivery, in person and on the page, had a hero’s swagger—he seemed to see himself as Perseus, swooping in to save art, the beautiful Andromeda, from the monster of political correctness. Hickey writes wonderfully, but I think theorist Abigail Solomon-Godeau was correct when she called his book “yet another version of a very old game that operates to privilege a particular group of critics (almost all white men) as having access to the truth.”(1)

Hickey was on to something, though, in how he talked about beauty.

Words of Mystery

Joachim Wtewaal, Perseus Rescues Andromeda, 1611

As I recall, he said “beauty” was one of a special group of words that can’t be pinned down, as enthusiastically as theorists may try. These words are out of the mind’s reach because they refer to experiences that arouse the body as well as the brain. In this, he argued, “beauty” is akin to “love”: a mystery, a fog that obscures the rational landscape of what we think we want (the walks on the beach, the shared religion, the two kids…) with an intoxication of the heart. Beauty, for Hickey, is something that grabs us.

It didn’t occur to me at the time that “knowledge” might fit into Hickey’s group of words with elusive boundaries. It seems like no word should have sharper edges than the one with the dictionary meaning “the perception of fact or truth; clear and certain mental apprehension.” (2) But, just as arguments about beauty inflamed the nineties, a “discourse” about knowledge is heating up art now, troubling the curators and writers charged with trend-spotting to sort it out.

Words of the Hot and Bothered

Curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev dedicated Documenta 13 to “artist research…[recognizing] the shapes and practices of knowing of all the animate and inanimate makers of the world.”(3)

Yuko Hasegawa, curator of the 2013 Sharjah Biennial, writes about the “production through art and architectural practices of new ways of knowing, thinking and feeling.”(4)

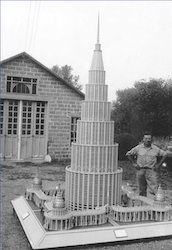

Marino Auriti with his model for “The Encyclopedic Palace,” a building he conceived to hold all the world’s knowledge

Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director of the upcoming 55th Venice Biennale, has named that show “The Encyclopedic Palace,” after a design by the self-taught Italian-American artist Marino Auriti. Gioni explains his choice by saying Auriti’s “dream of universal, all-embracing knowledge crops up throughout history…Today, as we grapple with a flood of information, such attempts to structure knowledge into all-inclusive systems seem even more necessary and even more desperate.” He intends the exhibition as “a reflection on the ways in which images have been used to organize knowledge and shape our experience of the world.”(5)

Can One Grapple a Flood?

Why such attention to art and “knowledge,” now? Gioni offers a clue. At first, his word-image “grappling with a flood of information,” seems discordant. Isn’t there a better word than “grapple” to use with “flood,” something more watery than “grasping” or “holding tight”? As waters rush over me, I will sink, or swim, or thrash, but I probably won’t “grab” or “grapple.” My hands know they can’t hold water. And right there, in the experience of the hands, is another clue.

“Knowledge” is not only words on paper, not just bits of information. It has a bodily component, just like “beauty.” We may not remember, but as babies we learned our world by touching it, tasting it, grabbing it. As adults, if we can’t use a piece of information, can’t “act on it,” we don’t really “know” it, not in the deepest sense. This is not just a philosophical opinion; researchers in fields such as anthropology, psychology and neuroscience are converging on descriptions of “thinking” that include “feeling.” As cognitive psychologists Frank Keil and Kristi Lockhart write, “We understand how most things work and why they are as they are as a consequence of how we interact with them.”(6)

So Gioni’s word choice is perfect. We tend to use “hand’ words, “grapple” and its relatives, to talk about knowing or “grasping” reality. Our problem, when we are “flooded” with information, is that there is so much information it “runs through our hands.” We cannot channel the flow into the groove of hand and mind working together; we cannot “get a grip”. So we are looking around, through the arts and sciences that we use to understand the world, to “get a handle” on knowledge.

Constructive Interference

Not coincidentally, art and science are coming into phase again, after a few decades when new art and new science didn’t have much to say to each other. There were always a few creative people ferrying between domains, but after a mid-century moment when cybernetics and systems were hot topics in both fields, artists pulled away. For the investigations of power, mass media, and identity that occupied late twentieth century art, “science” seemed either irrelevant or part of the problem. But now, as the information flood washes through, rearranging our culture, some artists and scientists are riding the same waves. One of those waves, which we’ll ride next time, might even deposit us in a place where Dave Hickey and Amelia Jones can both be right.

Not that Hickey cares any more. Having announced his retirement from art punditry with an excellent curmudgeonly flourish, he is off to… integrate art and science. “I’m proficient in math, and statistics, game theory, symbolic logic and all of that. I want to write a creative writing book about the statistics of literary prose accompanied by software so you could compare the statistical shape of your writing to that of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Charles Dickens, Ray Carver or David Foster Wallace,” he told The Observer.

There is much more to be said on the subject of knowledge and contemporary art, but for today, we’ll leave it there. Come back next time and we’ll dive deeper into those digital waters, perhaps surfacing with a pearl of knowledge.

1. Amelia Jones, “‘Every man knows where and how beauty gives him pleasure”: Beauty Discourse and the Logic of Aesthetics”

2. Dictionary.com

3. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Artistic Director’s Statement, dOCUMENTA(13),

4. Sharjah Art Foundation press release

5. Venice Biennale press release

6. Keil, Frank and Kristi Lockhart, “Getting a Grip on Reality,” Ecological Approaches to Cognition: Essays in Honor of Ulric Neisser, ed. Eugene Winograd, Robyn Fivush, William Hirt, Larwrence Erlbaum Associates, London, 1999, 187

7. Douglas, Sarah, “Dave Hickey is Retiring (Sort of), Observer.com, October 24, 2012