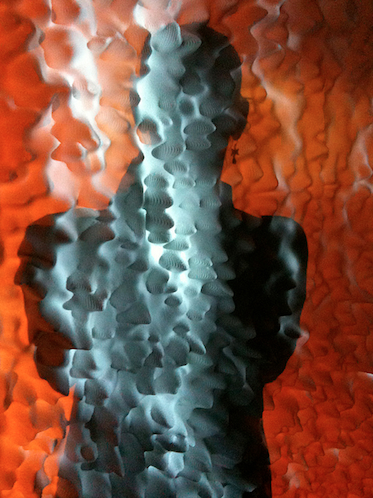

Almost a year ago, I walked into an evening in the Canadian Rockies, disguised as a small installation space at UCLA’s Art|Sci Center gallery. It was a peculiar experience—how could it be that this windowless room held a mountain evening? Nothing in view seemed “natural.” An expanse of white foam with a curious surface, peaked like stiffly beaten egg whites, leaned against the wall. Two projectors sent surges of color over the foam, cycling through sunset orange to grey blacks and back again. The sight was intriguing. But if that were the whole of the piece, it would not have been a landscape.

And it was a landscape, although not a scene in classic perspective, not something that, with a bit of imagination, one could walk into. It was, perhaps, a sideways landscape, the blurred stream of peripheral vision. But it was not my eyes telling me that I was “outdoors.” It was my ears. An amazing array of sounds recorded in the “quiet” of a remote Canadian twilight signaled “you are in a wild place.”

Detail of Dark Skies by Patricia Olynyk with Christopher Ottinger and Axi:ome (2012), showing laser-carved foam projection surface

Sound locates us in space. Sound designer Walter Murch, famous for his work in the movies, once said that if you needed to let the audience know that the dark space the character was in was a vast parking garage, you just had him drop a penny. The sound of the coin hitting the floor would delineate the space, hard and echoing, in the mind of the “viewer.” We have such a basic need not-to-bump-into-things that our brains take care of sound processing speedily and “unconsciously,” before we have “time to think.” Thus the sound was important to the effect of the piece. This much I understood almost immediately. But what was it, exactly, that the sound was telling me?

The Joy of Lingering

Circumstances allowed me to spend the entire afternoon with the installation, soaking it in with a rare amount of leisure. I’ve been thinking about Dark Skies, as artist Patricia Olynyk titled the work, at odd moments ever since, remembering the feel of wild dusk and something else I couldn’t quite put into words. It’s been luxurious, slow thinking, just letting the memory of the piece return when it wanted to, mulling over the experience and then letting it sit some more.

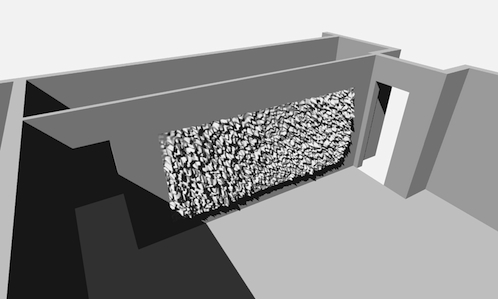

Digital model for Dark Skies, showing the position and proportions of the projection “screen” in the installation space

If I were writing a “review,” this would have been a poor approach. As I write now, I wish I could hear the sounds again, the better to describe them. For such details, memory is not to to trusted. In writing reviews, detail and speed are virtues; they are a form of news. Accuracy and currency matter. But, focused on speed, one sometimes sails right past other things that could also be important. With time, memory identifies those things, eroding experience into very personal shapes, heightening some meanings and letting the rest go.

In ordinary life, if we think about this process at all, it is usually to bemoan the “lossiness” of our memories, not to consider the shape of what remains. But in the prologue to Memories Dreams And Reflections, the memoir he wrote at the age of 84, Carl Jung offered a different view, saying, “Recollection of the outward events of my life has largely faded or disappeared…That is why I speak chiefly of inner experiences…I can understand myself only in light of inner happenings.”

As the “outward event” of Dark Skies faded a bit in my memory, what would it leave behind as an “inner happening”?

Uncanny gravity

The strongest lingering impression of the piece was of something uncanny; “uncanny,” in the same sense that roboticists use the word. A robot that appears almost human is disturbing in a particular way. It triggers the responses we automatically have to other humans, at the same time we know we shouldn’t have them. This tension prickles at the backs of our necks, telling us in an animal way that something is off. Despite its beauty, Dark Skiesstruck me as strange in that way. And it was a real puzzle why that should be. Unless I blocked the projection with my shadow, nothing visible was “almost human.”

Detail of Dark Skies by Patricia Olynyk with Christopher Ottinger and Axi:ome, with the shadow of the artist

From Olynyk’s artist’s statement, I knew that the foam peaks were the shape of something animal and microscopic: the taste buds of a wild mouse. They might also be interpreted as steep mountain peaks, depending on how far away one imagined they were. The waves of color sweeping over the “taste buds” tracked the sun as it dropped below the horizon. They hinted at the cosmos. Just as the mouse taste buds were micro and macro, the flow of light might have been macro and micro, the passage of days or individual pulses of energy.

But there have been many works of art with oscillating scale. Sonata of the Stars (c. 1907), a painting by Mikalojus Čiurlionis, or Beginnings, Frosted Window, Rochester, N.Y.(1962), a photograph by Minor White, come to mind.

Mikalojus Čiurlionis, Sonata of the Stars, 1907

Minor White, Beginnings, Frosted Window (Rochester, New York), 1962

They offer wonderful experiences, but they are not uncanny. What Dark Skies has that they don’t is sound. The sound of Dark Skies makes the mind hum with spatial information, tethering it to an earthly locale, at the same time that the sights of Dark Skies take it out of this world, to places the mind cannot perceive directly. One’s consciousness can neither respond in a unified way to the bodily sensations or float free in imaginary space; it is caught in the in-between. Thus, the prickling hairs, the sensation of strangeness.

Attention and Memory

As I was ruminating on Olynyk’s work, I encountered the research of neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley. “Attention and memory have traditionally been viewed as distinct processes and have been studied independently,” he writes, “However, attention is a gateway to memory in that attended stimuli are better remembered than those that are not the focus of our attention… Sensory input from our surroundings often demand our attention based on stimulus characteristics such as novelty or salience (bottom-up processing), but we are also capable of directing attention toward or away from encountered stimuli based on our goals (top-down modulation).”

Hidden there in the language of research is another way of describing the “slow thinking” I have been sharing with you. The chance opportunity to thoroughly “attend to stimuli” gave me rich memories of Dark Skies, which tugged at my attention due to the novelty of the bodily, spatial experience it triggered. Spurred on by the goal of investigating “slow thinking,” I directed my attention back to the sensations over and over again, until my “top-down modulation” hooked up with my “bottom-up processing” in an “ah-hah!” moment. THAT, that twisting, slightly dizzy sensation of being in space that keeps moving from micro to macro, that is the “strangeness.”

Postscript

I haven’t said anything about the meanings Olynyk ascribed to the work, which centered around the distortion of natural rhythms caused by light pollution. The dizzy space I experienced might represent the dislocation experienced in always-illuminated environments by species who depended on the cycle of light and dark to organize their lives. But like most memorable artworks, Dark Skies can be interpreted in several ways.

The version of Dark Skies I saw was a prototype, a model for a larger, even more immersive installation. The full-scale piece remains a goal for Olynyk, but here is video of her earlier architectural-scale installation, Sensing Terrains, at the National Academy of Sciences.