This short picture-essay was a provocation for the “AI and Art” panel organized by Piero Scaruffi for the Codame Art + Tech Festival curated by Vanessa Chang, which took place at The Midway in San Francisco, 7 June 2018. The essay has been revised slightly for publication.

A Trio of Twins

To begin, I will juxtapose several images that we can use to think with.

1. Drawing from “Dream Vortex” (2011-ongoing) displayed in front of rococo painting

Image 1. These ghostly twins are almost as disembodied as the mathematical figures they contemplate. Those figures consume their world, almost blotting out their surroundings, although around the edges we see that there are still growing things and sky and space and a messenger of emotion, in the form of Cupid. Take these twins to represent the history of Artificial Intelligence (AI) research, absorbed in exciting yet discarnate models of human mind.

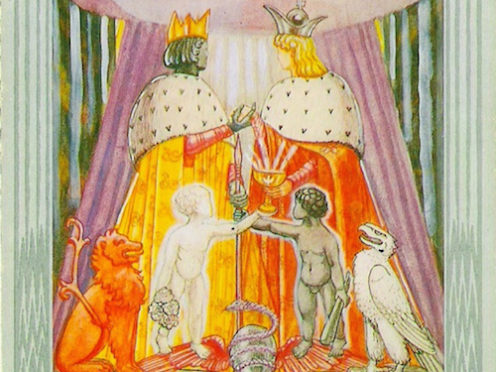

2. Detail of “The Lovers” card from the Thoth Tarot, painted between 1938-1943 by Lady Frieda Harris, directed by Aleister Crowley

Image 2. Think about what it means to be a mind without a body. You don’t have to believe in astrology to find a clue to this mystery in the psychological pattern “Gemini,” represented on this Tarot card. The twins of Gemini symbolize intellect, which, in its pure form detached from emotion and practicality, easily sees two or more sides to every issue. If we humans had only our minds to guide us through life— no emotions or physical cues — we might endlessly pursue our thoughts, never able to choose and act. There are people with neurological illnesses in this pathologically indecisive condition — the physician Oliver Sacks describes such a case in one of his essays. It could become the condition of artificial intelligences, should they approach the threshold of consciousness in a disembodied state.

3. Jean-Honoré Fragonard, “The Swing,” ca 1767, displayed in front of contemporary drawing

Image 3. Let us imagine what art could do for AI, by bringing art into the foreground. The two young people in The Swing, a famous 18th century painting by Fragonard, are all about the senses, alive to and absorbed in play, sensuality, and the natural world. What if we were to challenge an AI to interpret this painting, these concepts, and so to struggle — through many failures — towards its own concepts of embodiment?

The Challenge

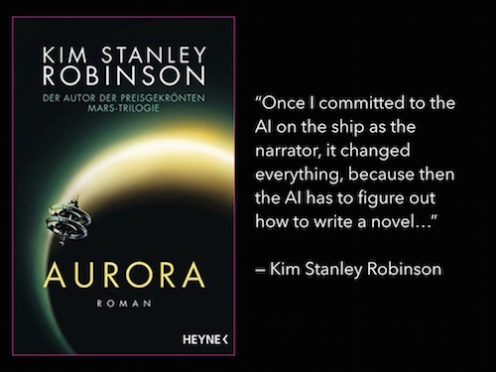

A similar challenge, posed in literary terms, is at the core of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Aurora, in which a ship’s AI enters the story as a dull, if capable, functionary. Its engineer commands the AI to narrate the story of the voyage; through many attempts and many years it explores, with great difficulty, the challenge of telling its story. In the process it develops agency and experiences something that might be emotion, something humans might call love.

Cover of a German edition of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Aurora, with a quote from Robinson interviewed by Sarah Lewin

How would one pose such a challenge to an AI with visual art? We might start with the way humans develop their ability to really see art, which is by looking and talking, by noticing, questioning, and exchanging. Sometimes the exchange is internal — What does that mean? Why is that woman’s face green? Where did that idea come from? Sometimes the exchange is external, social, a conversation with other humans. There is a lot to talk about in the endless differences in what we perceive.

Visitors discussing the work of John Cage at Crown Point Gallery, San Francisco

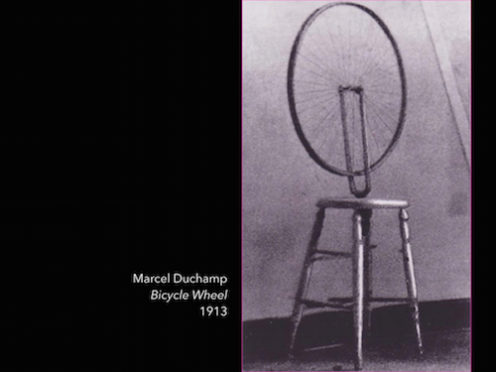

Contemporary art, in particular, tackles issues of categorization that might challenge an AI discovering its agency and existence. Take this work: is it a bicycle wheel, a kitchen stool, an act of play, an aide to relaxation? (The artist Marcel Duchamp, who made it, said he loved to turn the wheel and watch it, as if it were a fire.) Can it be all those things and art, too? Confronting that question has transformed many human minds — could an AI make the jump?

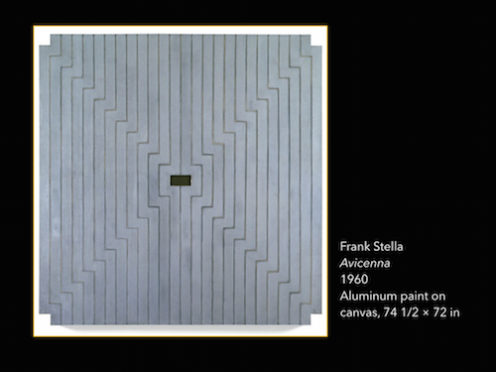

Perhaps an AI would even have a head start on seeing this work, a painting by Frank Stella.

Particularly when it was first made, humans had become so used to thinking of paintings as being the illusion created on their surface, they forgot that paintings are physical — layers of oil and ground minerals supported by wood and fibers. Stella helped us see painting’s physicality anew.

Particularly when it was first made, humans had become so used to thinking of paintings as being the illusion created on their surface, they forgot that paintings are physical — layers of oil and ground minerals supported by wood and fibers. Stella helped us see painting’s physicality anew.

The Question

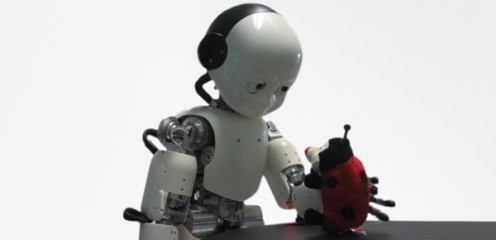

Could we give art to AI? Perhaps descendants of the new generation of embodied AIs, which some researchers are encouraging to develop as children develop, by interacting with the world around them and integrating feedback from their body with their thoughts and feelings, could accept such a gift.

iCub, the humanoid robot developed at IIT as part of the EU project RobotCube. It can see and hear, and has the sense of proprioception (body configuration) and movement (using accelerometers and gyroscopes).

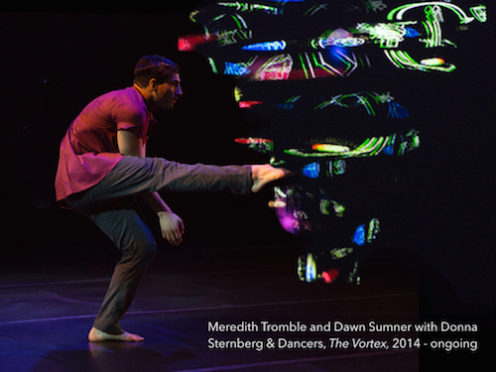

An AI that played — like a child picking up a marker and touching it to paper or like this human dancer playing with an interactive image vortex — would, I think, be close to consciousness.

Art is a powerful way for humans to explore mysteries, surprise ourselves, consider the things that we cannot control, and expand our individuality by encountering the world’s overwhelming plenitude. There is much to gain from offering this gift to AIs. Even if the offering “failed,” making it — seriously and experimentally exploring the possibility — would add to our knowledge of human art. And what if we were to succeed? Art that expressed AI experience would be a remarkable window into a different form of being, a form that we must try to understand.

Art is a powerful way for humans to explore mysteries, surprise ourselves, consider the things that we cannot control, and expand our individuality by encountering the world’s overwhelming plenitude. There is much to gain from offering this gift to AIs. Even if the offering “failed,” making it — seriously and experimentally exploring the possibility — would add to our knowledge of human art. And what if we were to succeed? Art that expressed AI experience would be a remarkable window into a different form of being, a form that we must try to understand.

The Now

We’re not there yet — as a reality check on my proposition’s practicality, take a look at “Visual Chatbot” with research scientist Janelle Shane’s commentary, posted on ai.weirdness.com. I won’t spoil the fun for you, but I will report that so far, Chatbot’s most human-like quality is that “When confused, it tends not to admit it.” Nevertheless, a relationship between art and AI is on the horizon — Shane offers T-shirts “designed” by neural networks. I’ll be wearing the one with the slogan “Sudden Pines” while waiting for the AI that can tell me what it thinks of The Swing.

###

Links

State of the Art Podcast. At the Codame Festival, I continued the conversation with State of the Art interviewer Andrew Herman, who also spoke with well-worth-hearing artist/engineers Alexander Reben and Ken Goldberg. My segment starts about 18m in.

Going Stellar: Q&A with Author Kim Stanley Robinson

Intelligent Machines That Learn Like Children, Diane Kwon (from Scientific American, March 2018. Requires subscription to access full text.)

An AI That Knows the World Like Children Do, Alison Gopnik (from Scientific American, June 2017. No subscription required.)