Right now someone is destroying art. Clearing out a studio, a house, or a storage unit and pitching art into the trash. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but the factors that determine which art escapes, which artists receive credit for their work and which of their works are carried forward, bear inspection. All the exhibitions in the massive Pacific Standard Time (PST) initiative were about retrieving art for history (as you know if you’ve been following Art & Shadows, PST was a Getty-funded extravaganza that engaged more than sixty institutions in telling the story of art in Los Angeles from 1945 to 1980); it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to observe such an intense effort to rescue art for history. For me personally, the PST exhibition State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970, curated by Constance Lewallen and Karen Moss, stimulated the best questions about the history-making process.

A Short Detour into Game Theory

I come to this topic fresh from a talk by computer scientist Jon Kleinberg about his research on the allocation of credit in scientific communities. As he described his model, which is based in game theory, I imagined changing his subjects from “scientists” to “artists.” He seemed to be giving an accurate description of the way one artist’s work becomes worth saving and another’s… not so much. Kleinberg himself probably wouldn’t make this leap without data. But I’m just going to jump.

Jon Kleinberg, computer scientist and MacArthur Fellow, lecturing at Cornell

His research is reported in a paper called “Mechanisms for (Mis)allocating Scientific Credit,” co-authored with Sigal Oren. Kleinberg and Oren open by saying it is thought that the expectation of credit motivates scientists to choose certain lines of research; therefore explicit and implicit forms of recognition (awards, publication, respect) shape the questions that are asked and the knowledge that is gained. Then they raise an issue: “The allocation of scientific credit, however, has also been the focus of long-documented pathologies: certain research questions are said to command too much credit, at the expense of other equally important questions; and certain researchers . . . seem to receive a disproportionate share of the credit, even when the contributions of others are similar.”

Let’s try reframing the “pathology” as “Certain artistic questions are said to command too much credit, at the expense of other equally important questions; and certain artists seem to receive a disproportionate share of the credit, even when the contributions of others are similar.” Well, exactly. Charles Darwin, meet Alfred Russel Wallace and Marina Abramovic, meet Barbara T. Smith.

The Drive for Credit

The belief that credit for major trends in 20th century art was unfairly distributed was arguably the driving force behind PST. Witness this quote from Getty Foundation Director Deborah Marrow, from a 2008 press release: “The exhibitions . . . will demonstrate the pivotal role played by Southern California in national and international artistic movements since the middle of the twentieth century.”

The belief that credit for major trends in 20th century art was unfairly distributed was arguably the driving force behind PST. Witness this quote from Getty Foundation Director Deborah Marrow, from a 2008 press release: “The exhibitions . . . will demonstrate the pivotal role played by Southern California in national and international artistic movements since the middle of the twentieth century.”

Can you imagine a foundation devoting ten million dollars to exhibitions demonstrating that between 1945 and 1980 New York artists played a pivotal role in national and international artistic movements? No one would question the premise and no one would care—it’s a thoroughly uncontroversial idea, and it would take a lot more than ten million dollars to challenge it, although I don’t know why one would try—it’s true.

But it is also true that California in 1970 was a hotbed of adventurous art, some of which was internationally recognized at the time, and it is true that, as Lewallen writes in her catalog essay, “…during succeeding decades, the group of artists identified with the beginnings of Conceptual art was narrowed, and, with a few exceptions, California Conceptual artists were less likely to be included among them.”

Threaded throughout State of Mind are several “got-there-first” stories: the first show of Body Art (“Body Works,” Museum of Conceptual Art, San Francisco, 1970); the first “post-studio” program in an art school (led by John Baldessari at CalArts); early street performances by Linda Montano and Bonnie Sherk that, according to Lewallen, “implicitly challenged the prevailing male hegemony even before the full thrust of feminist art inspired body-centered work by women on both coasts.” And speaking of feminist inspired body-centered work, there’s Barbara T. Smith, whose performances Nude Frieze (1972) and Feed Me (1973), resemble and predate much more famous works by Maurizio Cattelan and Marina Abramovic.

An important artist?

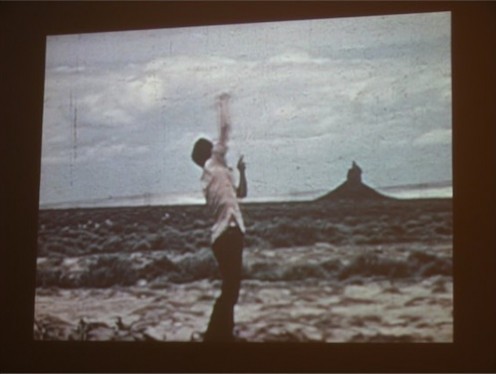

The curators have to address “who got there first,” but you might, like me, find it rather a dead-end question, given the simultaneous emergence of conceptual art in several art centers around the world. Whether or not Paul Kos was the “first” anything, he made amazingly poetic works that are just getting better with time. The wry futility of Roping Boar’s Tusk (1971), a one-minute film loop in which Kos stands in the foreground, repeatedly attempting to lasso a rock formation that is visually close but physically distant, is intensifying as the look of the original Super-8 film stock becomes antique. The evident age of the piece heightens the Sisyphean quality—it’s been years and he’s still out there, still trying to catch that rock/answer/insight.

Paul Kos, still from Roping Boar’s Tusk , 1971

Super-8 film transferred to video; one minute loop. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, CA

That’s not the only way Kos’s work is aging well. In the student blog “Connect the Dots“, Brandon Ahlstrom interpreted Kos’s Sound of Ice Melting (1970/2011), an installation involving microphones, ice, and amplifiers, as “a humorous take on climate change.” This surprised me. I never thought about it that way although it’s struck me as an important piece since I first encountered it. The gestural arrangement of the microphones, crowding in to listen to the ice, merges several intertwined themes: the difficulty of comprehending slow processes, the limits of technology, and the passage of time. It’s possible, of course, that Kos was thinking about climate change in the early 1970s, but I’ve not seen an early discussion of the piece in those terms. His themes translate meaningfully into contemporary commentary because they run deep through our culture.

Paul Kos, Sound of Ice Melting, 1970/2011

Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

Based on the quality of his work, Kos qualifies as an “important” artist. Yet research in the credit-assigning mechanisms of the art world—art history surveys, art markets, exhibitions, and awards—would show that his level of recognition is far below that of “heavyweight” contemporaries such as Vito Acconci or Bruce Nauman. What gives?

The Kleinberg-Oren Model

Kleinberg and Oren propose that the seeming “unfairness” in the distribution of scientific credit persists because it benefits society. After working through a game theory model of competition and credit, they summarize their findings: “individuals choose among projects of varying levels of importance and difficulty, and they compete to receive credit with others who choose the same project. Under the most natural mechanism for allocating credit, in which it is divided among those who succeed at a project in proportion to the project’s importance, the resulting selection of projects by self-interested, credit-maximizing individuals will in general by socially sub-optimal . . . [Our] results suggest how well-known forms of misallocation of scientific credit . . . serve to channel self-interested behavior into socially optimal outcomes.”

They show that random distribution of credit is just as counter-productive as the fair distribution of credit. As far as society is concerned, there’s a sweet spot in the middle, where the abilities of many researchers are channeled into solving a variety of problems because they each believe they might receive a lot of credit for their efforts. “To each according to their contribution” isn’t nearly as successful as “winner-take-all” in getting the most people working the hardest on the widest range of scientific problems. And according to Kleinberg and Oren, “when certain individuals are unfairly marginalized by a community, it can force them to embark on higher-risk courses of action, enabling beneficial innovation that would otherwise not have happened.”

If you want details, here’s their paper.

Does it work for art?

Stephen Kaltenbach, ART WORKS, from the Sidewalk Plaques series, 1968/2005

Bronze. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell

This sounds a lot like the art world to me, although I can think of a few problems with translating their model directly to art. Are artists motivated by the expectation of credit? Particularly in the 1970s and particularly in California, there were quite a few practitioners who were programmatically anti-credit. Lewallen cites artist Stephen Kaltenbach as resolving to “become a legend quietly—in disguise, and through the back door,” reporting that Kaltenbach left a “promising career” in New York to teach in Sacramento, carrying on his conceptual activities “in private ways.” But he was still interested in becoming a legend. And it’s anecdotal data, but given the anguished comments I’ve heard from artists who could have been included in State of Mind and were not, when credit is on offer, artists like to receive it.

One might also ask if artists tackle “projects” in quite the same way that scientists do and how the model changes for a group-oriented culture, and if the subculture of artist groups such as Ant Farm is powerful enough to complicate the motivational picture. But exceptions do not necessarily disprove the rule, and as Kleinberg and Oren point out, their model is simplified, even for the scientific world. Perhaps a better question is so what? Does the “why” of unfair distribution of credit matter? I’ll come back to this question to next time, with more on State of Mind.

Tour Schedule: State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970

Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery

Vancouver, British Columbia

9/28/12 – 12/9/12

SITE Sante Fe

Sante Fe, New Mexico

2/23/13-5/20/13

The Bronx Museum of the Arts

Bronx, New York

6/23/13 – 9/8/13