When computer scientists Jon Kleinberg and Sigal Oren came up with a theoretical model showing that assigning credit unfairly resulted in the most productive creative community, they were thinking about individual scientists and credit in the form of prizes, high-status appointments and publications, and “good reputation.” But as I played with applying their model to the art world, I began to think the process they were describing might be work at larger scales, too, and wondered how it might relate to art history.

Like individuals, artistic communities have reputations. I’ve been writing about a 10 million dollar effort to redress a regional reputation, the Pacific Standard Time (PST) initiative. The Getty Foundation funded it to “demonstrate the pivotal role played by Southern California in national and international artistic movements since the middle of the twentieth century.”

And yet…a quibble here…many of the sixty-plus PST exhibitions included artists from Northern California. A few of them, including State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 (co-organized by the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archives and the Orange County Museum of Art) and Under the Big Black Sun (organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art), intended to address the entire state. Other PST shows were just sprinkled with artists who became Angelenos for the purposes of the exhibition.*

I noticed this “unfair” subsuming of one artistic community within another, but although it was amusing I didn’t think it mattered very much. I chalked it up to a problem with the way the Getty framed the research program, and gave props to the curators who tolerated messy geography to get at more important things. Residence is not the only factor in “belonging.” It was Tony Labat, from San Francisco, who took “performance art” to the Gong Show, an absurdist talent show that often featured tongue-in-cheek acts such as Gene Gene, the Dancing Machine. Under the Big Black Sun included vintage video of Labat and co-conspirator Bruce Pollack going for the brass with everything they had, whacking boxes and tooting kazoos until they got the gong.

Tony Labat and Bruce Pollack performing on The Gong Show, 1978

Minus, Minus, Plus

The Gong Show was already an enthusiastic race to the nadir of performance. Did two negatives — satire plus irony — make positive “art”? It’s a question that, like the performance, won’t sit still, refusing to be answered. Labat’s and Pollack’s appearance still vibrates with the tension of forcing “high” and “low” performance together. To give you a sense of the aspirations they were tweaking, in the same year as their appearance, a magazine covering radical art started up in L.A., dubbed “High Performance.” The title expressed the desire for performance to be taken seriously, to be regarded as “high art.” Labat’s irreverence moved along the dialogue about art and media culture, in a form specific to L.A., whatever his street address.

It was a cool piece, one that, along with the rest of Labat’s work, wasn’t much recognized until his 2005 retrospective at New Langton Arts in San Francisco. In his review of that show for Artforum critic Bruce Hainley wrote, “It would prove useful to consider why and how Tony Labat wasn’t included in RoseLee Goldberg’s live art festival PERFORMA ’05… [Labat] should be a key figure in any history of artists using action to negotiate the role of media (television and video, especially)…”

Hmmm. Hainley doesn’t actually consider why and how Labat wasn’t included in the big-time live art festival that, as Art in America has written, has “revived legends” from 20th century performance art. We can take care of that, briefly, by referring to the model I’m pirating from Kleinberg and Oren: certain artists “receive a disproportionate share of the credit, even when the contributions of others are similar.” Labat’s work is covered under the second part of that phrase. He was and is part of an entire community of artists who contribute to “optimal social outcomes” by intensifying competition in the art world overall and breaking new ground, often without receiving credit.

Should We Care?

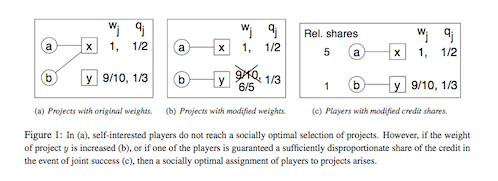

Figure 1 from “Mechanisms for (Mis)allocating Scientific Credit”

by Jon Kleinberg and Sigal Oren, 2010

Is that just the way it is? To recap, Kleinberg and Oren concluded that unfairness in awarding credit to individual scientists persists because it creates the most benefit to society overall. One could crudely rephrase their findings (apologies, Jon and Sigal): “There is always a fresh supply of researchers who think they could win the Nobel Prize. They all work like crazy on the “important” questions, so even though only one or two actually get the prize, society benefits from the concentrated depth of their research. And there is always another group of researchers who gauge their chances of receiving the prize as minus zero, so they choose offbeat questions, where they can be the big kahunas, and society benefits from the variety and breadth of their research.”

It’s a little cold for all the scientists — and artists — who are doomed to disappointment, recognition-wise. But creative people don’t need a game theory model to see that the game is often unfair, and a lot of them keep going anyway. Intrinsic motivation must count for something. Or maybe they’re just taking the long view. I’ve been speaking as if the recognition that artists receive in their lifetime and their place in history were the same things, which of course they’re not. Painters Hilma Af Klint and Arthur Dove, who like the more famous Wasily Kandinsky began making abstract art around 1911, are now receiving some of their due. All three are more interesting artists considered together, just as modern American art history gains from factoring Los Angeles and San Francisco (and Chicago and Boston and St. Louis….) in with New York.

At the same conference where I heard Kleinberg, there were also talks about new techniques in art history that may help us see such complex relationships more clearly. And maybe, eventually, affect the ways in which artists receive credit, although I suspect Kleinberg and Oren are correct that the system will always be stacked. So… to be continued, next time, with a look at Netsci 2012, coupled networks, and the exhibition Man Ray and Lee Miller: Partners in Surrealism.

***

* Double-checking my memory that I was running into artists I thought of as “Northern California” even in the exhibitions that didn’t explicitly include the entire state, I chose, at random, the catalog for Mex/L.A.: “Mexican” Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930-1985 to page through. At least five of the artists (Wallace Berman, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, Yolanda Lopez, Martin Ramirez, and Edward Weston) are also associated with the San Francisco Bay Area.