As I prepare to present art to audiences who may or may not care for my comments (sometimes referred to as “teaching art history”), I occasionally play with thinking of the lecture as a flower arrangement. The key works, the showiest blossoms, can be displayed in a subtle grouping with less-famous examples; sometimes a flamboyant spray of greatest hits is called for; sometimes isolating a work within a generous amount of space makes the most powerful point.

Working with images day after day, one notices customs of arranging them. Planting works in a furrow — a timeline — is the classic form, the usual metaphoric shape for an art history survey. Clustering is another favorite — bouquets of art and artists conceptualized as “styles,” “movements,” or “themes.” Occasionally works are strewn around like loose petals, as when I choose works for a studio class that will relate to student projects. In an advanced seminar, one work (escaping my botanic metaphor) might become the center of gravity around which all the other material orbits.

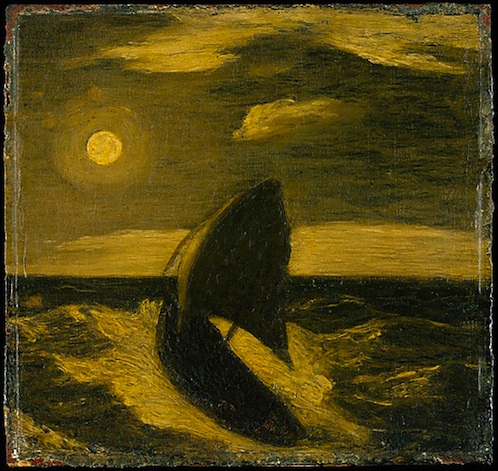

But none of these structuring forms capture the way one experiences works with which one has a meaningful relationship. I’ve loved Albert Pinkham Ryder’s dark seascapes since I first saw one in a book about art for children; at that first encounter I didn’t care about when it was made, Ryder’s thinking or nineteenth century American culture. I just liked to look at it. Other associations have piled up with time; I read his biography and recall just enough to know these are the works of a shy man who didn’t like to clean house; I’m no expert on America in my great grandparents’ day but I know a lot more about it than I did when I was a kid and I can picture Ryder’s New York.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Toilers of the Sea, ca 1880-85

Oil on wood, 11-1/2″ x 12″

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; George A. Hearn Fund, 1915

I can also look at Ryder’s work and think about how his seas compare to those of photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, or what his color relationships demonstrate about the biology of seeing, or bounce into musing on the incredible distances across which 19th century families sustained relationships — something that came vividly home reading a biography of the astronomer Maria Mitchell, who, like Ryder, grew up in a whaling community. (She had unusual opportunities for a woman of her times because the men were always out to sea.) I know I am lucky to be living in a time when this store of associations is possible. The richness and variety of the information with which we routinely engage works of art represents a new state of affairs.

Post-carousel art history

Somewhere among my possessions is a manila envelope holding a faded set of prints that was used to teach art history in the 1940s or 50s, before slide projectors came in. When I try to imagine how that worked, the method seems so impoverished. Did the class gather around to look at each print? Did every student have their own set? Even if they did, how constrained a history taught with thirty images must have been. Yet the first method I learned for teaching now seems poor, too.

The top shelf of my bookcase holds a leaning tower of faded yellow boxes, slide carousels for classes I taught between 1994 and 2001. The images in those carousels were not easy to get. Hours of locating color reproductions in books, photographing them, and dropping the film at the developer, not to mention picking up the slides, labeling and sorting them… so much labor. But slides and carousels are over, except occasionally as a medium for art, in the same way that platinum prints are over, except as an exotic medium redolent of the past.

There’s a shift in knowledge that corresponds with the turn to digital images. We are not just communicating the same old knowledge with new means. As any artist knows, form holds meaning; and the forms of our teaching hold meaning, too. In academic terms, I’m talking about the “material culture” of schools; in everyday words, one might call it “the stuff we use in the classroom.” Because the “stuff” we use now is mostly available anywhere at any time (and if you have any doubt, yes, I am talking about digital images, image search and the World Wide Web) it exerts an influence on everyone who is curious about art. The shape of the knowledge that we can have has changed; like my web of associations with Ryder, it is linked and omnidirectional: it is a network.

Material Culture and A Day Made of Glass

The artist Philip Benn, who did time in my classroom a few years ago, alerted me to an industrial film that envisions teaching with tools appropriate to a networked field of knowledge. You may already know it. The version Benn showed me was A Day Made of Glass 2; Youtube counts about four and half million views for that film and its predecessor (A Day Made of Glass 1), both from Corning, Inc.

Take a look — the parts I’m most interested in are the classroom and field trip scenes that run from 1:53 – 2:53 and 4:20 – 5:19 respectively. Imagine that instead of elementary school lessons, you are seeing properly scaled, life-size, high definition images of art, perhaps placed in a relevant environment. And that the display can move at least as seamlessly between material prepared by the instructor and material called up in response to student questions as the computer you are using to read this piece. (You might also imagine new art made specifically to take advantage of the mural-size display or tablet-environment connection, but I’ll stick with art historian dreams for the moment.)

Stills from classroom and field trip scenes, A Day Made of Glass 2

I know what you’re thinking. That jetpack that was supposed to fly you to work? Not in your garage. Prophetic visions of future technology do have a notoriously poor record of fulfillment. But a mismatch between film and feasibility is not inevitable — much depends on the goals of the filmmakers. Bruce Tognazzini, who was responsible for Starfire, a 1994 film similar in spirit to A Day Made of Glass, gives a fascinating voice-of-experience account of creating a film that really could come true. In the case of A Day Made of Glass, a degree of realism was in Corning’s interest, so much of the technology depicted is within reach.

The other critique one might raise has to do with the social costs of the technology — since the 1950s, a suspicious stance toward technological utopianism has been art world fashion and a valuable fashion it is, too. We should be thinking about the politics of lithium, the particularities of physical presence, inequities in educational access, and all the other sticky topics that gum up progress toward digital nirvana. It is, in part, my job as a contemporary artist and art writer to remember those questions. But it is also my job to help people develop their own rich network of associations with and through art. Tools that make drawing connections, as in my web of thoughts about Ryder, more fluid and natural? I can hardly wait.