The Elaborately Signaled Landscape of Desire

You don’t have to be human very long to know that there are desires that are explicable and then there are the other kind. Sometimes we are indifferent to “good things” and intensely drawn to certain trouble. The twentieth century believed, for a while, that Freud explained those inexplicable desires — in case, dear reader, you are a child of the 21st century, his idea was that they echoed our infancy — but the Freudian model of personality doesn’t look so trustworthy today.

As we investigate the immune system with biomarkers, examine the brain with nano-imaging, capture complex group thinking on video, and compare our society’s “givens” with the “givens” of others, studying ourselves at many levels, the very notion of a “self” is changing. We are beginning — literally — to see the connection between mind, body, and environment. Analyzing inner experience in terms of “id” and “ego” seems curiously antiquated, as if we were discussing physiology in terms of “humors.” We have new ways of talking about subjectivity, about moods, about attitudes and desires. As philosopher Alfred Tauber writes, “the self” has been left exposed as a metaphor, whose grounding — philosophically and scientifically — is unsteady and thus increasingly elusive.”[1]

It’s not that we have one successful metaphor to replace the notion of “self.” Current thinking on the matter resembles a heap of pieces from different jigsaw puzzles, a multitude of strangely shaped bits crying out to be sorted. “Self-perception theory” says that we observe our behavior in order to learn who we are, but we also protect our self images by “reducing cognitive dissonance.” There’s evidence for “behavioral priming,” the influence of environmental factors of which we are not consciously aware, “mirror neurons”, which the New York Times called “cells that read minds”, and “emotional contagion,” defined as a tendency to converge, emotionally, with another person.” And that’s just for starters. The one certain thing is that there doesn’t seem to be an inborn, essential self in control of human behavior. (Although some people have attempted to retread that essential “self” in genetic terms, as research progresses even genetic dogmas are unraveling into a snarled mess of contingencies.) So how are we to understand the experience that neuroscientist Antonio Damasio refers to as “knowing that this is me,” and the desires that arise from that awareness?

The Marriage of the Imaginative and Technological

To the list of factors complicating our understanding of “self,” curators Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari add technology. Their exhibition Ghosts in the Machine, at the New Museum, “examines artists’ embrace of and fascination with technology, as well as their prescient awareness of the ways in which technology can transform subjective experiences.”

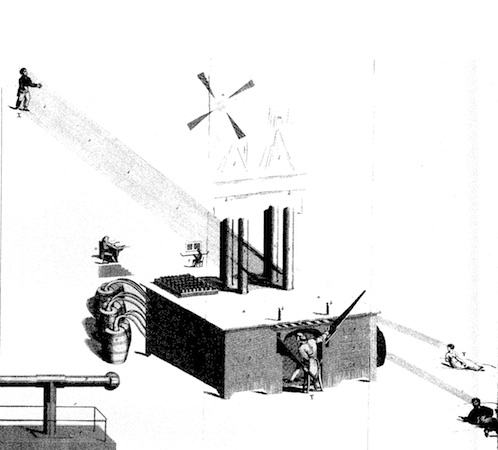

James Tilly Matthews, Engraving of the Air Loom, from John Haslam’s “Illustrations of Madness”, 1810. Ink on paper, 15 3/5″ x 10 1/3″

The oldest work in the show is James Tilly Matthews’s 1810 engraving of the “Air Loom,” a fantastic machine that Matthews believed was used by a cabal of his enemies to insert foreign thoughts into his mind. Among the newest pieces is Pearl Vision (2012), a video by Mark Leckey in which a drummer and his drumset merge kinetically and visually (via reflections in the shiny snare drum). These two works, old and new, bracket the emotional range in human-machine relationships: from monstrous invasion to blissful fusion.

Mark Leckey, still from Pearl Vision, 2012

HD Video and Installation

Our capacity to meld our sense of self with “inanimate” objects is pre-historic, at least by extrapolation from shamanic cultures one can make a solid argument that it is so. Thus one might question the curators’ conviction that contemporary identification with our tools is something special. But it is true that an artist such as Johanna Wintsch had to live in the 20th century to declare “Je suis radio” (“I am radio”), and particulars of form are everything in art.

Johanna Wintsch, Je Suis Radio, 1924

Embroidery, 16 3/4″ x 40 1/2″

Most of the works date from the mid-1950s to mid-1970s, a time when the cybernetic theories and computing technologies developed in wartime began to transform civilian life. The curators offer not only important works from the period but also restage fragments of influential exhibitions. Their re-presentation of these historic linkages between objects gives their exhibition exceptional depth. Source exhibitions include Arte Programmata (1962); The Responsive Eye (1965); Cybernetic Seredipity (1968); The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (1968); Art and Technology (1970); the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion at the international Exposition of Osaka (1970) and the performance/happening 9 Evenings (1966), defining moments all in Western art history. Deciphering engineer Herb Schneider’s drawings for 9 Evenings and sensing Robert Breer’s moving Floats (1970) behind me, while viewing a photograph of the original Floats hovering in the mists of Osaka, I tasted the excitement of the engineers who had new questions to tackle and the artists who had new ways to make things.

Living in an Enormous Novel

Speaking of defining moments, I’ve known that J.G. Ballard’s novel Crash and its derivatives (notably David Cronenberg’s 1996 film) were considered part of the canon of prescient art-about-modernity. But prior to Ghosts in the Machine, I gave them a miss; the elevator pitch for their relevance (erotic wreckage!) turned me off. Reviewers found Ballard’s ouvre transgressive and titillating; but like beauty these qualities are in the eye of the beholder and the reviewer usually seemed to have the eye of a suburban teenager. Reading between the lines, I deduced that Ballard’s work was tiresomely sexist and grossly romantic. Plus, having experienced a car crash, I had no time for glamorized accounts of the same. But I started watching Harley Cokeliss’s film Crash! (1971) before I read the label, and although I realized a few minutes in that the film must have something to do with Ballard (it is based on his 1970 novel Atrocity Exhibition and he plays the male lead), it gave me something that made the sad gender politics (it IS a classically sexist film) watchable.

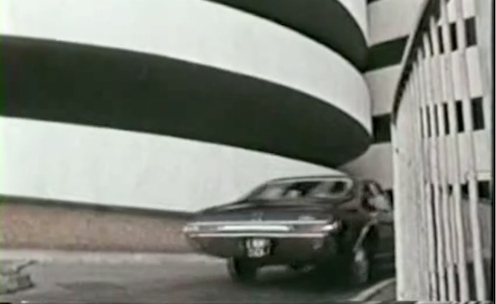

Harley Cokeliss, still from Crash!, 1971

16 mm Eastmancolor transferred to video, sound, 17m 34s

The film (which you can view here) predates the novel Crash, and as Ballard had a large hand in its making, it is considered part of his creative run-up to the more famous work. Juxtaposing ordinary driving scenes and crash test footage, Ballard lays out his thesis that “the experience of driving condenses many of the experiences of being a human being in the 1970s.”

A woman who, it is made clear, is a figment of his imagination and, as an object of desire, equivalent to the auto, experiences a car crash. Ballard reflects on the meaning of it all, his awareness perfusing the film even as he participates in it. “Are we just victims,” he asks, “in a totally meaningless tragedy, or does it [a car crash] in fact take place with our unconscious, and even conscious, connivance…It seems to me that we have to regard everything in the world around us as fiction, as if we were living in an enormous novel, and that the kind of distinction that Freud made about the inner world of the mind, between, say, what dreams appeared to be and what they really meant, now has to be applied to the outer world of reality…Take a structure like a multi-storey car park, one of the most mysterious buildings ever built…What effect does using these buildings have on us?”

Harley Cokeliss, still from Crash!, 1971, showing the carpark

Reading my question about “self” back into the film, asking how it appears in Ballard’s world, we find him intuiting pieces of the 21st century jigsaw puzzle “self.” The form of the film, with Ballard both observing and explaining his thoughts, could be “self-perception theory” at work — “we observe our behavior, then reach conclusions about who we are.” And that multi-story car park, the one that might be having an effect on us? It seems as if he knows, at some level, about “behavioral priming.” His proposal that we connive in the manufacture of death could be seen as “attributing motivation” or “reducing cognitive dissonance,” as psychologists name our urges to explain actions and to justify them, especially when we are wrong.

Contradictory Desires

In his own way, Ballard was chewing (or perhaps I should say “cranking”) on the conundrum of conflicting desires, noting that we act as if we simultaneously desire both life and death. We know that cars can kill us, but we love them anyway. In 1971, Ballard could have been thinking about global warming and alternatives to car culture; he could have been reading The Second Sex and questioning gender roles. Instead he burrowed into the contradictory desires he, as a man of his times, received from his culture, and contemplated their consequences without proposing a solution.

There I found the value of his work, especially in the context of Ghosts in the Machine. Every technology arises from desire; why would one go to the trouble of chipping rock or laying cable if there wasn’t something one wanted? Sometimes we think of technology as “answering” our problems, but we might do better to regard it as a message from our desires, a message that is in need of interpretation because we don’t really understand who we are. Of all the works in the exhibition, it is Crash! that makes the case for the importance of digging into the relationship between our desires and our machines.

Ghosts in the Machine runs through September 30, 2012 at the New Museum.

1. Tauber, Alfred, “The Biological Notion of Self and Non-self”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/biology-self/

FURTHER READING

Antonio Damasio, Self Comes To Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain

Home Page Image: still from Phillipe Parreno, The Writer, 2007, on view at Ghosts in the Machine