Remote Viewing

Living in this “global” art world, I think quite a lot about exhibitions that I will never see. I read catalogs, and look at websites, and talk to people who made it to Kassel, or Havana, or Gwangju. There is a small mobile village of people who keep up with all the major international exhibitions in person. The rest of us read the reviews, and, if we live in an urban art center, encounter the work that someone liked enough to put into circulation. There are benefits to being downstream. In a world where we have access to much more art than we could ever appreciate (according to critic Eleanor Heartney, viewing all the video art in the 2002 Documenta would have cost 600 hours), I can live with having the first cut made by passionate viewers who don’t mind living in airports. But I know that there is knowledge that can be transmitted second-hand and knowledge that can’t. That there is a gap between direct and mediated experience is a truism. But what is falling into the gap?

The gap is nothing new and it is narrowing — our understanding of art-far-away has to be better than when stay-at-homes got their art news from engraved illustrations. Sometimes it has been productive, as when a mis-reading of published photographs encouraged painters in California who were experimenting with very tactile paint surfaces. One of those young painters, Philip Linhares, who later became an influential curator, told me that when he was an art student at the California College of Arts in the 1960s, he and his fellow students looked for inspiration to the new magazine Artforum. There, Linhares and his cohort, which included Joan Brown, Jay DeFeo, and John McCracken, saw small, black and white reproductions of abstract expressionist paintings. Shrinking a photograph of a large painting to the size of a postage stamp concentrates the forms, and a black and white reproduction emphasizes contrast and texture, often making a paint surface look denser than it really is. This is not the only reason that artists like Brown developed the very physical paint handling for which they became known. But it’s not an insignificant reason, either.

This is a test…

Catalog for Ghosts in the Machine, published by Skira Rizzoli

If you’ve been keeping up with Art & Shadows, you know that I made it to “Ghost in the Machine” and had at least one opinion overturned — in the September 2 post, I confessed to an about-face on J.G. Ballard. But before I parse the viewing experiences, a word on the materials of the “remote view.” The catalog for “Ghosts in the Machine” includes the expected essays by the exhibition’s curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari (their essays are also posted to the Museum’s website and are linked below.) But it is atypical in that approximately three-quarters of the 368 pages are devoted to an anthology of historical texts related to the art. Think college reader — the anthology, assembled by William S. Smith, is just like the bound volumes of photocopied articles that college students used before readings were posted to course websites. And I mean just like them…the texts are reproduced as found, orientated every which way, with web site headers, advertisements, typos, and other artifacts of publication intact. One could think of this presentation as sloppy or one could think of it as conveying period flavor. It did draw attention to the means of reproduction, and thereby to our shifting infrastructure of machines.

I didn’t mind rotating the volume to read and the typos were rather enjoyable (witness this mutation of Marshall McLuhan: “When we pout our central nervous system outside us we returned to the primal nomadic state…”). But then I wanted to know what year the McLuhan essay — “The Agenbite of Outwit” — was first published. Given that McLuhan died on New Year’s Eve in 1980, I was reasonably sure that the only date associated with the text, 3/23/2012, was the date Smith downloaded it from a website. So — problem.

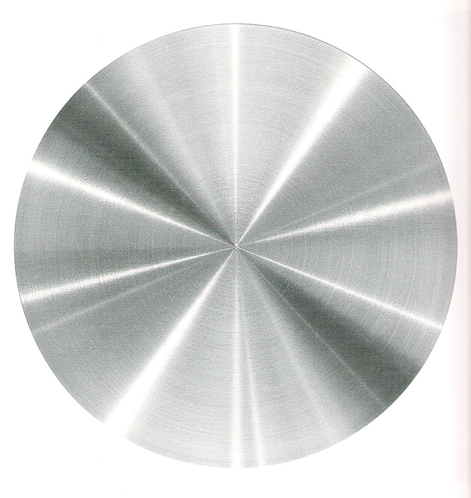

The plates were in color and generously sized, but they also suffered from information dissociation. Looking at the first image, I wanted a clue as to what the the metallic-looking Disco, by Getulio Alviani, might be. It was probably a sculpture, but it could have been a drawing. And was it the size of a Christmas ornament? A vinyl record? A tractor tire? These things matter. The captions gave only the name of the work, the artist, and the year. I did eventually locate the materials and dimensions, and the date of the McLuhan essay (1963), in a checklist and bibliography in the final pages of the book. But determination was required to orient the work in space and time, something that happened almost automatically in the exhibition.

Getulio Alviani, Disco, 1965

This is a result I did not foresee…

The exhibition didn’t always offer the best experience of the art, though. An installation by Richard Hamilton, Man, Machine and Motion (1955), which felt dead in the gallery, looked alive in the catalog photograph. This also seemed to be a matter of scale: in the catalog photograph, Hamilton’s original installation packed the room with a enticing maze of photographic blow-ups.* When that same structure was recreated for “Ghosts in the Machine”, in a larger space, it lost compression. The spatial tension leaked out of the ensemble, leaving a not-very-enthralling array of posters.

Above: The original version of Man, Machine and Motion Below: The New Museum version of Richard Hamilton’s Man, Machine and Motion, 1955/2012

Courtesy the Estate of Richard Hamilton

The catalog also offered a better experience — or at least an experience — of Grazia Varisco’s Schema Luminoso Variabile (Variable Bright Scheme) (1962-63) and Mark Leckey’s Pearl Vision (2012), two works that were down for the count when I first visited. (I did see the Leckey eventually, on my third visit, but the Varisco remained dark.) One might argue that such breakdowns are exceptions, but they aren’t really. Have you ever seen an exhibition of art that plugs in with everything in working order? I found it surprisingly hard to argue that the show itself was the definitive presentation of the art. There were moments when the catalog had the edge; material from both spheres fell into the gap between object and reproduction.

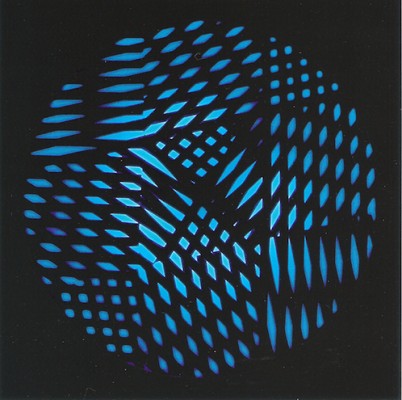

Grazia Varisco, Schema Luminoso Variable, 1962-63

Looking through my “before” and “after” thoughts, I found many subtle and curious dislocations. The ones that weren’t matters of time (one can’t imagine how pleasurable the computer films of Larry Cuba and Lillian F. Schwartz would be from a still) were almost all, in some way, matters of scale. I hear readers yawning even as I type this — it seems obvious that time-based works would suffer in reproduction and as a concept, scale doesn’t engage people as much as “symbolism” or “color.” But come back for the next Art & Shadows, and I will tell you why you should care, getting back to Stan Vanderbeek in the process.

* Yes, the impression that the original piece was more successful could have been due to the photography. I could be adding my mite to the heap of mis-read reproductions. But I looked carefully at both the installation and the photograph, and I’m taking the shot.

Ghosts in the Machine is at the New Museum through September 30, 2012.

LINKS

Ghosts in the Machine

Of Ghosts and Machines by Massimiliano Gioni

The Body is a Machine by Gary Carrion-Murayari